Developments in Immunotherapy

One of the hallmarks of cancer is its ability to evade the body's main line of defence: the immune system. In most cases, a mutated or irregular cancer cell will be identified via immune mechanisms and trigger a cascade of reactions, resulting in the death of the cell in question. For cancers to be able to survive and proliferate they must avoid or overcome such an immune response, as discussed in the Basic Immune Response section of the syllabus. Therefore, it is easy to see why immunotherapy is such an attractive target for new drug treatments.

Why have immune therapies been so difficult to develop?

Many researchers see immunotherapy as the future of cancer treatment; ideally, a new drug could assist the immune system to ensure that it is able to deal with cancer on its own accord, bypassing the need for more invasive or unpleasant treatments such as surgery or chemotherapy. Why, then, has this proven to be such a difficult task?

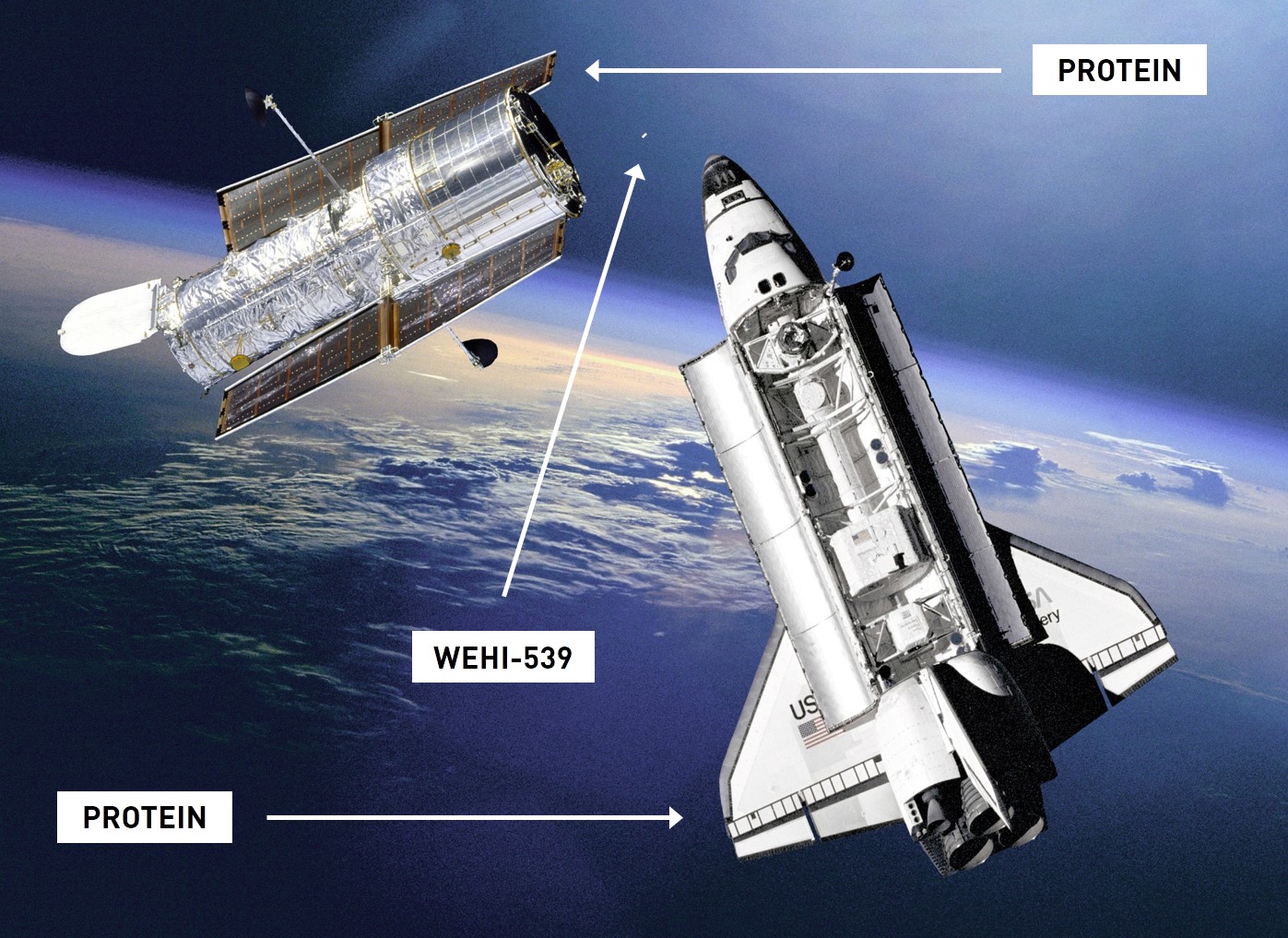

One such example of a novel immunotherapeutic drug recently developed here in Melbourne is WEHI-539. This is a relatively small compound that, when taken orally, is able to prevent the binding of two much larger proteins which. Under normal circumstances, the binding of these proteins is the signal for the immune system to not engage in apoptosis of the cell. Therefore, this drug is able to act such that the cancer cell is no longer able to escape the immune response. Drug therapies of this sort are difficult to develop because of the large size of the immune proteins in question. Imagine trying to stop a space shuttle from docking with a satellite by using something the size of a bolt. That is the nature of the challenge, but at a molecular scale.

The future of cancer treatment?

There are a whole family of other immunotherapies that must be given intravenously (infused straight into the bloodstream) because they are so large that they would be destroyed in the stomach if given orally. The most promising candidates of this sort are the monoclonal antibodies. Drugs within this family can be identified by the ending --mab. Monoclonal antibodies have little difficult affecting the large scale protein-protein interactions involved in the immune system as they themselves are large immune proteins.

These antibody proteins feature a common "Y" shape where two ends feature fragment antigen binding (Fab) regions and the third end has a fragment crystallisable (Fc) region. All of these regions can be modified to respond to a specific molecular target, known as an 'epitope'. These drugs are currently in use for a range of immune diseases, such as the drug infliximab. This antibody binds to a molecule abbreviated as TNF-α, thereby preventing it from binding to other immune proteins that would cause inflammation in conditions such as Crohn's disease and rheumatoid arthritis.

By simply modifying the Fab region to recognise the sort of molecules involved in cancers (T-cell receptors expressed on tumor cells, as shown in this study, for example) they could help the immune system locate and destroy cancer cells.

Potential problems

While monoclonal antibodies could provide an effective and much less invasive treatment for cancer, it would raise a number of other social and ethical issues. At this early stage monoclonal antibodies are extremely expensive to produce which may be prohibitive to many cancer patients around the world without access to healthcare. Even in the case of countries such as Australia with relatively robust healthcare systems this may prove to be an issue; should the drug be accessible for free via the pharmaceutical benefits scheme (PBS) it could cost the taxpayer many tens-of-thousands of dollars for each cancer patient. In a future where half the population could potentially require such treatments in their lifetime, it's hard to see how this could be afforded alongside an aging population and other global economic concerns.